Growing Grass on Iceland: What is behind their government's extensive support of sport?

Football pitch next to a live volcano? Nothing mind-worthy in Iceland. Voluntary sport is made by the public for the public. It is encouraged, supported, and socially incorporated.

This island presents by far the best example of a model for sport as a public good, one that could be taken as inspiration for multiple other countries. But could it really be repeated elsewhere?

Messi miss

This was the second peak, right after the Euro 2016 quarter-finals.

To draw with Argentina.

No more words to say — we remember what it meant for them, with 10% of the population right there, at the World Cup.

What made this nation unite behind sports? Why were they an inspiration to ultra groups around Europe to mimic their ‘Viking’ clap?

In 2023 Iceland allocated approximately 3.3%1 of total government expenditures towards sports and other recreational services — more than any other country within European Economic Area (EEA).

It’s all about the people

In the economic justification for such sport funding, the public must be on par with what the government has in mind. The longer the policy is active, the more probable it is for the society to jump on track with it. And it seems like the Icelandic people not only jumped on track - they took their sport identity by storm. This brings us back to the most important factor in any efficient public policy: there has to be human capital developed, or at least developing, to be able to fulfil set goals. Icelanders did just that. And of course, ultimately, some historical milestones may have helped.

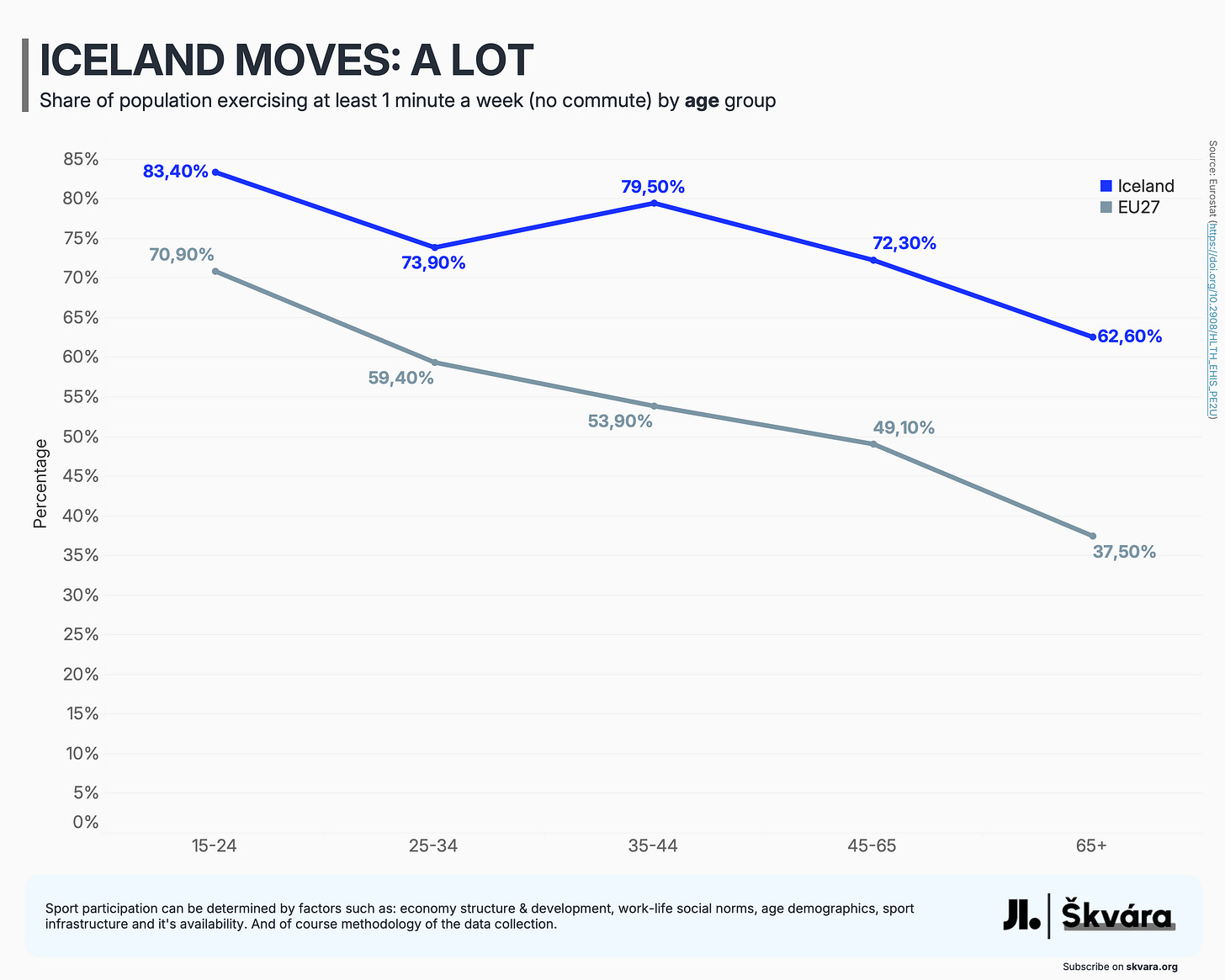

In the most recent dataset from Eurostat for sport participation, Iceland is up there in the top quantile. Compared to the EU27 average, regular activity isn’t something people here are afraid of. But what is behind all this activeness?

If you have a research question, ask Reddit. For sure, with the respondent sample in mind, few interesting ideas popped up.

The story starts in the 2000s, when the government was facing a long-term problem with teenage binge drinking. In such a small society, it is easier to focus on these problems — and they also spread much faster. As a counter-force to drinking, the Icelandic government chose a different motivator.

This was achieved partly through encouraging kids to participate in organized hobbies like sports.2

Frístundakort

This is rather special case of public policy specialising in children’s sport. Frístundakort - the “recreation” card - allows children aged 6-18 from all socioeconomic background to participate in after-school sport activities. These habits then transfer into adulthood. The subsidy (75k ISK) can cover basic annual clubs’ fees. The question is: what is the impact of this subsidy on the prices of connected services and goods — training fees, travel, clothing, etc.? Depends on:

How elastic is the demand for children’s sports?

The aim is for all children and young people in Reykjavík ages 6-18 to be able to participate in recreational activities regardless of their economic and social circumstances. The Recreation Card is intended to increase equality in society and diversity in the practice of sports, arts, and leisure activities.

- Reykjavík website

The country is small and ethnically uniform; thus, transaction costs in establishing any common goals are lower. A smaller community also creates stronger network effects within the economy, speeding up the process of the “multiplication” of positive externalities. Information transfers quickly and efficiently, unlike in more diverse, politically unstable, or simply larger countries prone to ‘Chinese Whispers’. The financial crisis may also have played a role through encouraging participation in more ‘economical’ sports like running, gym, and football. In years of higher unemployment, some groups of people could kick-off similar shifts in sports participation as seen after the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Indoor Mania

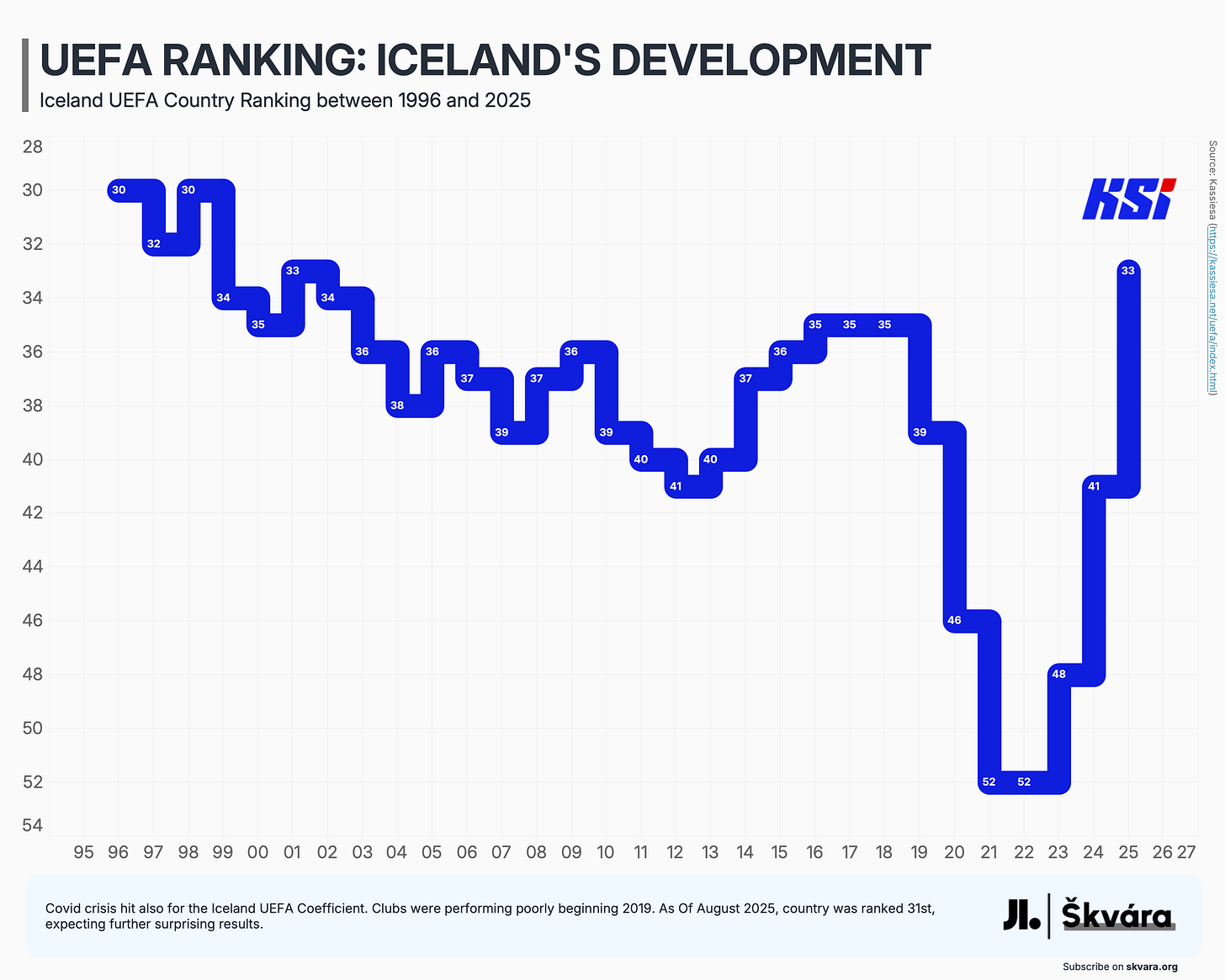

Outdoor heated turfs, indoor halls, and other necessary infrastructure were essential to kick off the football craze. How else would you be able to tackle the geographic and meteorological nuances of living in Iceland? A natural experiment in its purest form. It is debatable whether the success stories of Iceland’s national team during the 2010s can be attributed to this unprecedented infrastructure3. But for the current and future generations, it is considered a symbol of the Icelandic transition in sports as a whole, and of the football body – KSÍ (Knattspyrnusamband Íslands) in particular.

All of these ‘soccer houses’ come with one small detail: they cost a lot to run – far more than a regular grass pitch in Central Europe. Operational costs for this immobile capital take up a significant chunk of the government’s sports expenditure.

What is in there for other countries?

Media coverage of Iceland during the Euros and the World Cup reached unprecedented highs. The country is just waiting for another major success to revisit these topics on the global stage. But the mills are still running even today. Was the golden football generation solely the product of politics emphasising an active lifestyle? Professionalism grew, and so did the players. There are possibly more sporting accomplishments cooking for the Icelanders. Recent shifts in Iceland’s UEFA Country Ranking for club competitions might give us the clue.

The crucial problems in reproducing such politics in other countries are:

Scalability: larger population → more interest groups → less consensus.

Current sports habits of different social groups: what if the country simply doesn’t have the resources – be it financial, logistical, or biological?

Other – more relevant – society-wide pressing issues.

Shape of the demand curve for children’s sport: if inelastic, no reason for intervention.

Geography.

On the other hand, the inspiration-worthy challenges Iceland overcame:

It’s all about cross-government partnerships. The state, regions, and municipalities should have at least compatible views and programmes around sports subsidies for the young generation.

Infrastructure with economics in mind first: multipurpose halls and pitches instead of purpose-built facilities. Using what already exists, instead of waiting for new things to come.

Climate in mind.

And most importantly.

It all begins with the kids.

What might be biggest Icelandic takeaway for your country?

Enjoyed this post?

If you’d love to see Škvára bring sports economics insights to more people who shape the game — an ☕️ espresso always helps!

LOVE this!!! I’ve been similarly advocating for young adults, people out of primary education years, to join team sports to help with the depression and “hopelessness” happening in young adults in the USA.

Excellent piece. Really enjoyed it