Village Theatres of Dreams: Do EU Funds Help Where It All Begins?

These are the grassroots. The "quiet" workforce of sport. People with the biggest hearts for the game they chose. What is the role of EU funds within this environment? Are the subsidies needed?

In the debate around sport financing, there may not be enough emphasis on the place where sport is most vulnerable: at the beginning.

Focus is on the professionals

In sports economics, the overall understanding of public subsidies for professional sports is clear. No national arena, nor Olympics is able to cover the government subsidisation through the economic benefits within the city and neighbourhoods. Many studies have shown that these benefits are acquired only by very targeted subjects. Athletes - obviously - but also local small businesses, infrastructure developers, sports agencies, etc. have gained relatively more from such mega-projects than the public in general. Professional sport is, by definition, professional. It's meant to remain more privately owned.

It's not true that the Paris Olympics or development of Stadion Narodowy in Warsaw have not created any positive side-effects. Some form of subsidies are justifiable, but those projects often relied on state funding of more than 50%. We are all sport fans; however, we see these projects differently. If only economists were to run national sports agencies, nothing of this scale would be organised or built and sports clubs would carefully calculate ROI of increases in stadiums' capacity by 10s, not 1000s.

But! Now shift our minds to today’s football training session.

Coach said no balls today

The compressor’s broken.

Interpretation of government costs changes with respect to amateur sport. Sport is crucial for children's development. Benefits from attending sports clubs by youngsters are often observed later, even for those who don't follow with a professional career in sport. Sense of motivation, perseverance, grit, success and failure in sport often prepare them for future life's ups and downs. But here we are now, the kids are still young. Some of the mentioned benefits come earlier, some of them come late. We know they will, but the families of those kids may not, at least immediately.

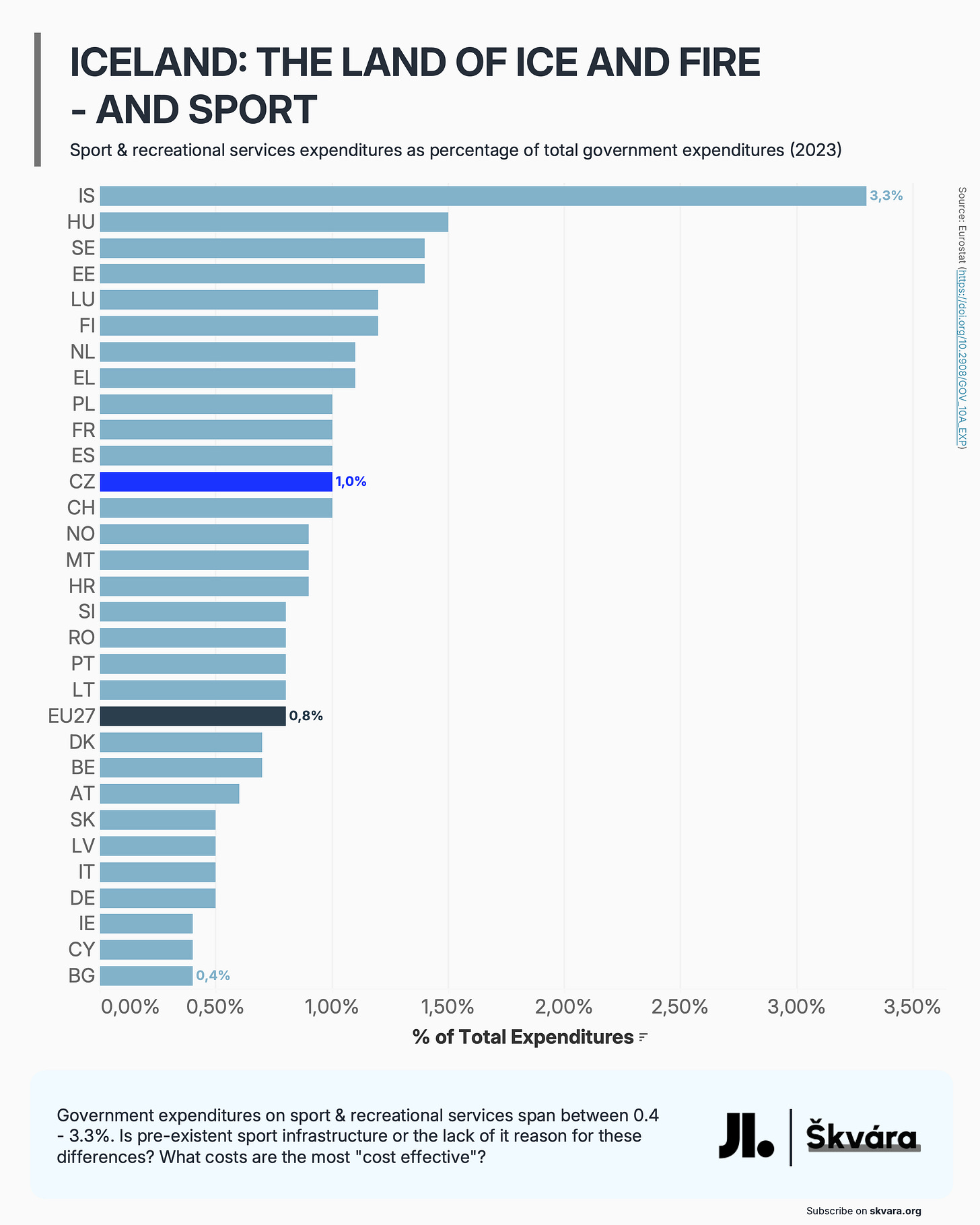

Governments in the EU spend approximately 0.8%1 of their total expenditures on recreational & sporting services on average. Iceland is worth a separate post.

→ If the families' tax payments would decrease by 0.8%, thus disposable income would increase, and parents would maybe not see their kid's future in professional sport, would they all be willing to pay the full price for training, equipment and bus trips to neighbouring villages? Would sports participation increase or decrease? This is not only true for children, is it? The benefits from this participation are applicable for all ages and for all sports, even recreational hiking and cycling. But the future generation is in this topic the most important.

Economic benefits of kids' sport activities then spill over to all areas of life. That itself makes it worth supporting.

Of course, there are cases where being part of a bad group pushes you to make bad choices. But we can agree that for children who can, sport or anything else more physically demanding will always be better than pursuing, let's say, less wanted pastimes. Also for society as a whole. And with that, government and city council subsidies to local sport clubs or investments into sport infrastructure are (reasonably) justified.

Where is EU’s place in sport then?

Because sport should be accessible for all, the EU steps in2. Next to regional and state governments. European Regional Development Fund or programmes like Erasmus+ might have played their part in enhancing sport experience in your local town or village. Be it new seats for the small stand behind one of the goals, running water in locker room showers or volleyball nets for the sand pitch nearby. These small projects make the lives of village sport heroes that much better and make sport that more inviting overall.

This is a sports economics publication, thus it is our duty to think more in terms of economic effectiveness. Sport subsidies in terms of amateur sport are justifiable, but the justification itself has its limits. Research is on this ambivalent depending on the efficiency measures chosen34. Nothing is worse than an unused cycling path for the price of millions of € per kilometre.

And do not forget potential corruption behaviours.

How to measure the impact of sport subsidies?

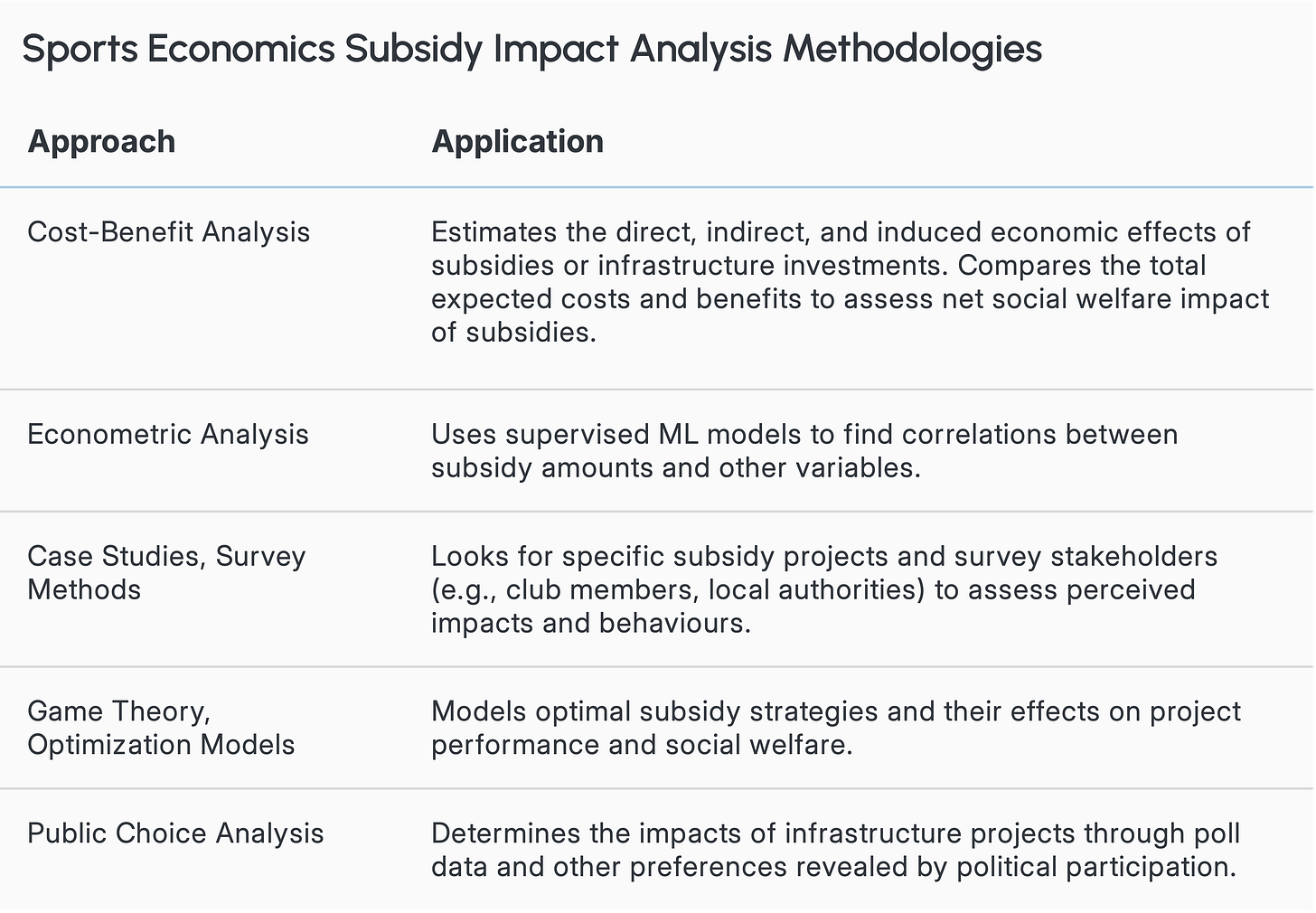

The methodology possibilities for determining this economic viability are endless. Here is a snapshot of what current sports economics uses:

Cost-Benefit Analysis

Econometric Analysis

Case studies, Survey methods

Game Theory, Optimisation Models

Public Choice Analysis

With that, back to the studio.

We have the tools indeed. We apply them on a case-by-case basis, but literature on subsidising amateur sport is for now limited. But from what we know, we can say that they do help, to an unspecified degree. There are unspoken rules to get the money where it's most needed, that no exact redistribution table can replace. We must find those rules. It's in our best interest, so the government bill is nothing but pharmacy expenses.

Enjoyed this post?

If you’d love to see Škvára bring sports economics insights to more people who shape the game — an ☕️ espresso always helps!

Footnotes & Further Reading

European Union, P. O. of the E. (2016, September 22). Study on the contribution of sport to regional development through the structural funds: Final report. Publications Office of the European Union. [Link]