The Anatomy of a European City of Sport

Marbella, Rijeka, Leuven, Trebinje, Strasbourg, Tábor, and Nymburk. Only a handful of cities have been awarded this media-covered title. Is it just marketing—or is there something more to it?

City officials send an official bid, add documentation on the current state of local sports infrastructure and year-round sporting events. ACES representatives then come visit the place, and a decision is made. Annualy, multiple cities and towns are awarded the titles: European Town of Sport (for towns up to 25k inhabitants), European City of Sport (for cities between 25k an 500k inhabitants), European Capital of Sport (awarded to one city), among others.

What economic value do these awards actually carry?

Is the award a prerequisite for increased funding of local sports clubs and venues if this new ‘sticker’ is now assigned to the city? Or is the title about validation only? Could it inspire people to move there envisioning an active lifestyle for themselves and their children? Or is it just another award (tool) for policymakers to increase their chances of serving another term?

Let’s focus on the core economic components of these cities, as they are assessed on criteria such as sports infrastructure, enabling movement for citizens of all ages, experience in organising prestigious international and/or regional sports competitions.

Spending on sport. But how much?

The main driver of sports development in any city is public and private investment synergy. In best scenario, the multi-layered sporting, economic, social and urban goals of local clubs can’t collide with politicians’ views on city’s future. The key to effective partnerships are transfers from public institutions which, depending on the size of clubs, may cover a large amount of clubs’ budgets. The percentages of city budgets assigned to the development of local sports also differ based on city size. Usually, the larger the city, the lower the percentage. Smaller towns tend to subsidy clubs using between 2-3%12 of their budget. Larger between 1-2%.3

There currently is no verification of the hypothesis that expenditures on sports facilities and public funding for sports clubs—as a percentage of the city budget—differ for cities with and without those European … of Sport titles. This research would require thorough categorising of each chosen city’s expenditures. Transparent council accounting will hopefully be a norm in the future. Currently, there are tools for the analysis of public procurements that could leverage automatic tagging for sport-related agreements.

The titles have more of a multiplicative effect: they support what was, rather than create what wasn’t.

All coins have two sides

Cost-Benefit Analysis (without numbers) of acquiring the title for your city in summary:

1. The Title Itself

➕ Commitment to sport for all; excellent for marketing and media.

➖ Raised expectations create risk of broken promises.

2. EU Cooperation

➕ Access to funding and partnership opportunities.

➖ Complex bureaucracy and compliance requirements.

3. Public Sports Infrastructure

➕ Long-term public good and community benefits.

➖ High upfront costs and maintenance burden (CapEx, OpEx); risk of underutilised facilities if not well managed.

4. Private Sector

➕ New sponsorships; increased public spending.

➖ Dependence on public spending.

5. Macroeconomic Impact

➕ Higher property values and local business growth; stimulates sports tourism and related economic sectors (hospitality, retail).

➖ Risks from poorly planned continuous stakeholder engagement.

6. Public Engagement and Demographic Effects

➕ Higher public interest to take part in local active lifestyle; may increase city immigration.

➖ Citizens may not understand or value the initiative if sport hasn’t been a topic before.

Sports infrastructure from the sky

The cities are evolving. What was a rough football pitch with rusty goalposts just a minute ago is now a modern, floodlight-lit astroturf. New playgrounds for kids have more versatility than your local gym equipment. The best way to see where the money is flowing is to look for clues in satellite imagery. Sports investment is a long-term game, but due to positive externalities, it is a game to be played.

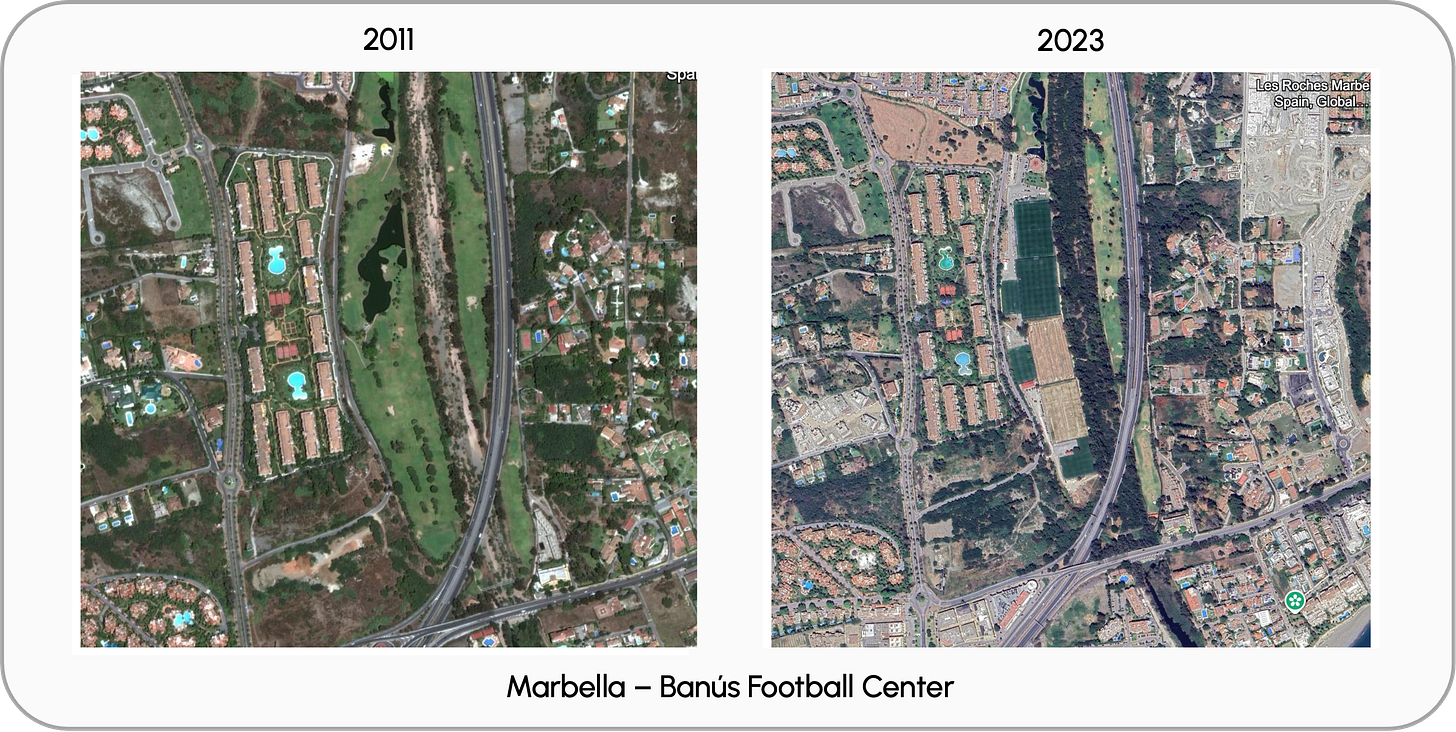

Why did Marbella become the go-to place for top-tier football clubs during their pre-season? Apart from its geography and climate, it was the public-private cooperation that led to the development of football centres in the 2000s. The relatively new Banús Football Center is one example. Marbella became such a haven for football clubs because the city council enabled the private funding of such infrastructure.

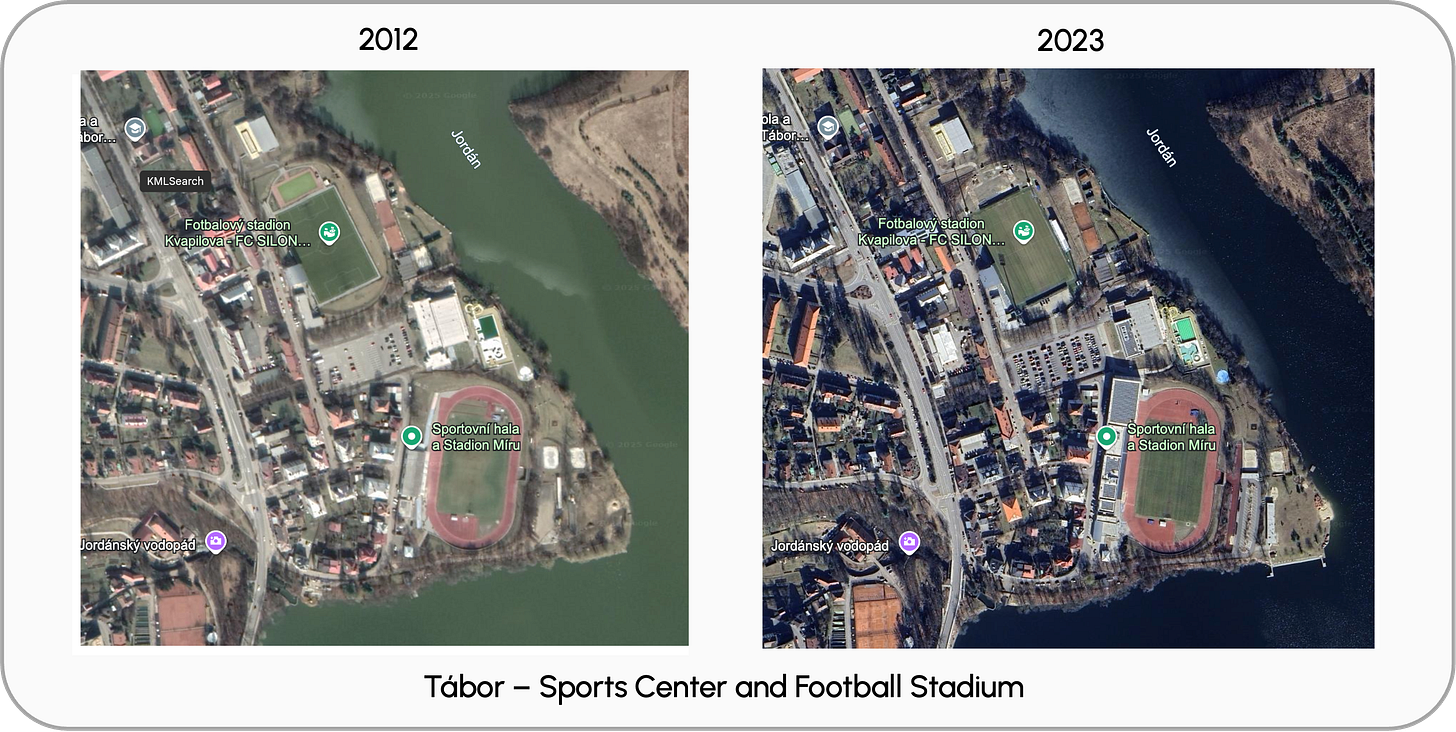

The changes within public space can sometimes feel a bit unseen from the outside, but they burden the city accounts nevertheless. In Tábor, Czechia, a new town sports hall was opened in 2021, but more upgrades (sustainable energy, parking lots) were also made to the nearby athletics stadium and its surrounding buildings.

Where to next?

Just pick a city for a round trip, buy a beer and sausage at their Sunday League game, support the love of locals for the occasion. Visit grandparents and take them to a local park, see how people spend time outside. Eating, drinking and/or sports. Or exercise.

People use public space to take on sporting activities, thus it is in the public interest to shape surroundings so more and more people (and future ones) can do so as well. Titles such as European City of Sport aren’t an empty promise. They shape the city’s reputation. They help in securing more funding for sport-related projects. And then, it is up to the stakeholders to determine effective ways to put the finances to good use—weighing the opportunity costs for the city, for respective business owners, sponsors and themselves.

In the European context, the EU is this game’s key player, especially via The European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)4. But more on that some time later.

Next time you see a new padel court in your neighbourhood, you may ask yourself—why did it happen?

What do you notice about sports with respect to your environment in general?

Further Reading

Matušíková, D., Švedová, M., Dzurov Vargová, T., & Żegleń, P. (2020). An Analysis of the „European City of Sports” Project and its Impact on the Development of Tourist Activity: The Example of Selected Slovakian Cities. Turyzm/Tourism, 30(1), 61–70. [Link]

Teixeira, M. C., Mamede, N. B., Seguí-Urbaneja, J., & Sesinando, A. D. (2023). European Cities of Sport as a Strategic Policy for Local Development of Sports: A Perspective from Sports Management in the Last Decade. Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research, 103(1), 28–43. [Link]

Footnotes

City Assembly of Trebinje. (2023). Rebalance of the Budget of the City of Trebinje for 2023. [Link]