Revenue is King. Multiply It. Understanding Club Valuations – Part Two

One simple number. Easy to remember, easy to grasp. Are analysts able to find a suitable equation that leads to a meaningful enterprise value? And what actually shapes the chosen revenue multiplier?

The ever changing ownership landscape in world football is worth a note. By Christmas, your favourite club will probably be sold and bought approximately twice. To help you prepare, Škvára resumes with the next chapter of the club-valuation puzzle.

Club owners’ already in possession, or entrepreneurs keen to join the owners’ ‘family’ are in desperate need to value their business periodically. The previous part, focused on the Discounted Cash Flow model with Slavia Prague as an exampl, shed a light on the problematic nature of football markets and why state-of-the-art valuation methods often fall short in this business, or in sport more broadly.

Next up. Revenue.

One could argue the key company metric. Without revenue, there’s no need to save costs, you simply can’t afford to have costs at all.

The methodology behind the revenue-multiple method is quite simple: you multiply the annual revenue by a certain number to arrive at the estimated valuation.

The question: Is there an approximate universal multiplier for any club in any league?

Yes and no.

Revenue is only half a Story

The yes answer to the previous question has a value of 4.

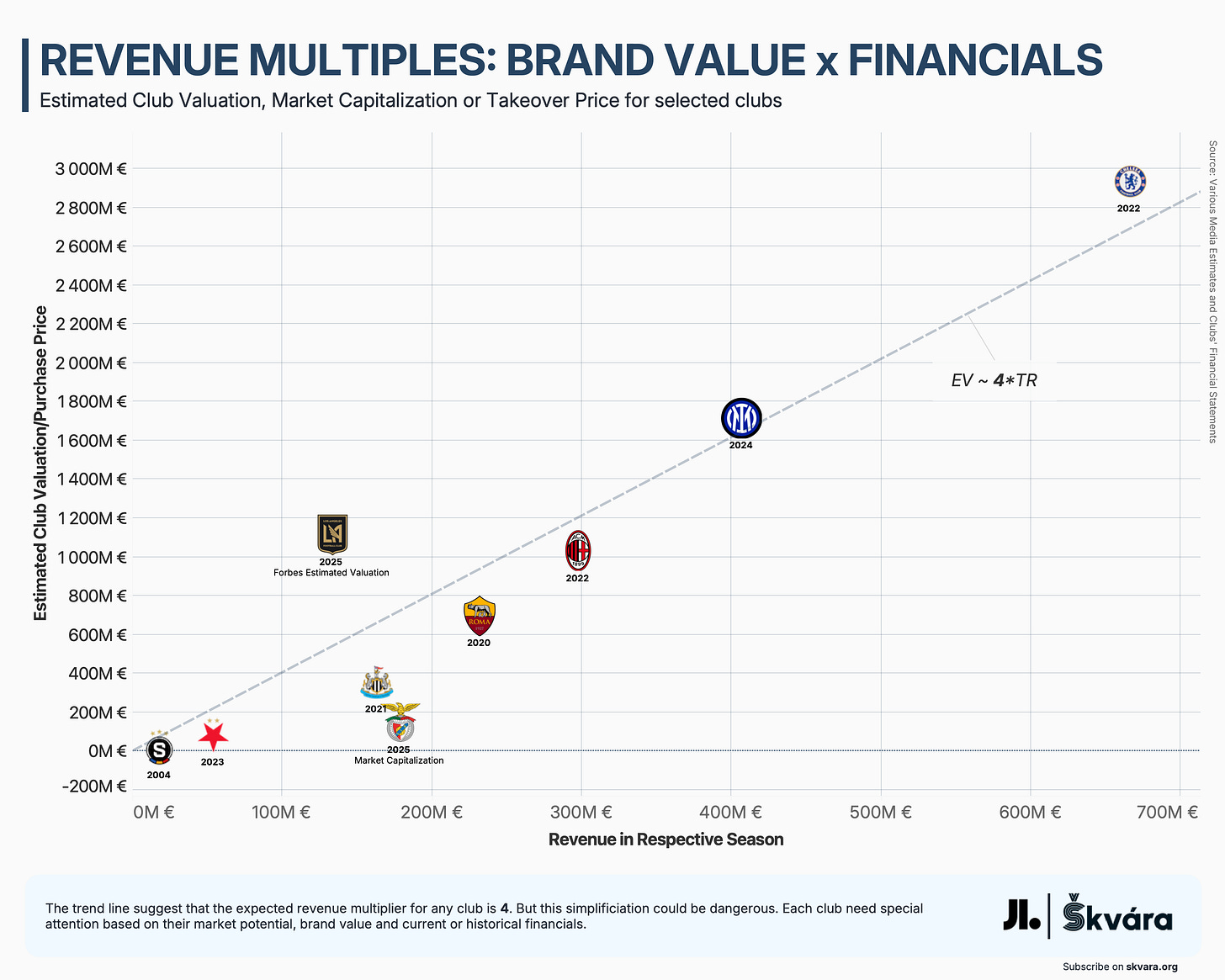

In the following scatter plot, the relationship between clubs’ estimated valuation and respective total revenue for the pre-takeover period is shown.

Valuations can be either:

estimated by media - LAFC,

calculated using proxy market capitalisation - SL Benfica,

copied from takeover price - Chelsea FC, or

inferred from purchase price of less than 100% of shares - AS Roma.

Unfortunately, the variation of this simple linear model is quite high. It’s perfect that we can assign revenue multiples ex post; however, club owners need to know the value today — before tomorrow’s takeover.

MLS clubs like LAFC can’t be mixed with European clubs, especially due to the unique factors of US & Canada sports leagues. In the case of LAFC, the simple fact of playing in a closed league generates a revenue multiple within the 9–10 range — more than double the standard. On top of that having extensive support from Latin-American citizens as well as the upcoming generation also helps.

For enterprises that are not yet profitable or whose earnings are inconsistent, revenue multiples emphasise future opportunities over current profitability. A true startups.

On average, football clubs’ values are four times the amount of their current total annual revenue. This is on the low end in comparison to other industries: high operational costs, fluctuating revenue, and embedded uncertainty leading to higher overall risk. This valuation discount can often be a reason why owning football clubs might seem like a good way to diversify a portfolio of the very wealthy or investment funds — provided the owner is not, in fact, risk-averse.

During Covid the reality for many clubs around the world was clear: how to keep the ball rolling. Any valuation estimates around the year 2020 would miss the reality quite a bit. Period from 2019 to 2021 deserves its own special valuation model.

The Rest is Risk

The risk is simply still there — and for smaller football enterprises even more prevalent.

Smaller or mid-table clubs with rich histories, playing in the top tiers of the European football league system, often fail to generate Free Cash Flow (FCF) consistently each season. This is why previously discussed Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method isn’t well suited to this industry. For initial estimation, enterprise value divided by a club’s annual revenue comes in handy.

Some football revenue is certain — except during major world events. Additional revenue can also be relatively secure if the club can rely on a loyal fanbase that will not abandon their colours the first time the team enters a difficult period results-wise. If the season’s kit design is at least slightly different from generic catalogue offerings, it gives that revenue certainty a small boost.

Broadcasting revenue depends on broadcasting deals and, of course, on whether the club secures participation in European competitions and/or plays near the top of the table. For mid-table clubs, broadcasting income can even be the most predictable element, as leagues are locked into multi-year agreements. Changes in player contracts and revenue from player sales are the opposite of predictable.

A club’s fundamental financial health can’t be determined by one metric alone. This is why both revenue multiples and operating income, or EBIT, work best in combination. But historical revenue — especially from continuing operations — remains the strongest predictor of long-term value.

Beyond Profits & Losses

But again, it would not be wise to have one metric only to determine the value of reality. Your value would equal how much you make, not what you do. The most noble things often go unmonetised or unnoticed. A sports club’s value is often a play of multiple factors that exceed financials. This is not a rational business at first glance, at least not yet. If it was, sports investment funds would already be established within financial markets.

However, subtle hints that sport is growing into a respectable asset class can be seen through the recent rapid changes in ownership structures and the “celebrity” status that comes with them. Political scientists call it sportswashing; economists call it economic rationality.

In the end, the analysis demonstrates that a modern football club is a paradox. It is both a sophisticated, multi-billion-pound global business and a living, breathing emotional entity. The full picture includes the club’s heritage: its history, its community, and the emotional connection that defines its fanbase. Working with the local community is the first step. The masses come afterwards.

👉 Follow-Up in Part Three

The story is more complex and thus deserves multivariate models for club valuations.